Nature Photography

Science Communication Projects

Photo Stories (2025 Photo Calendars)

Photography

Do you notice how bubbles cause two opposite reflections of its surroundings? No two bubble photos will ever be the same.

A huge school of Big-eyed jacks (Caranx sexfasciatus) swarm divers in the renowned marine reserve of Cabo Pulmo, Mexico.

Dive guide looking into a crevice near the entrance of cenote X'batun in Yucatán, Mexico.

A grey whale (Eschrichtius robustus) spy-hopping our boat in Puerto Chale, Baja California Sur, Mexico.

A whale shark (Rhincodon typus)—the biggest fish in the ocean in the Mexican Caribbean. Swimming with them is an undeniably unique experience if done responsibly, and photographing them is no easy task!

A blue morpho butterfly (Morpho peleides) in Costa Rica's Diamante Eco Adventure Park.

A pink flamingo (Phoenicopterus ruber) in Celestún, Yucatán—an iconic species important for ecotourism in the region.

A green iguana (Iguana iguana) makes eye-contact at Costa Rica's Diamante Eco Adventure Park.

A humpback whale fluke (Megaptera novaeangliae) in Canada pierces through the ocean surface along the same horizon as Mount Baker in the USA.

A vibrant reef in La Paz, Baja California Sur. Can you spot the curious red fish in the foreground and the divers in the background?

A blue agave (Agave tequilana) in Tepoztlán, Mexico radiates a beautiful blue at dusk after rainfall.

Rocky skies — lake reflections in Mount Seymour, Canada yield a new perspective.

A wild howler money mother (Alouatta palliata) and her young chimp swing through the trees in Guanacaste, Costa Rica.

A young and playful California sea lion (Zalophus californianus) pirouettes in front of SCUBA divers in Los Islotes, Mexico.

Slack-liners practicing at Cenote Yaakun in Playa del Carmen, México.

Pacific herring roe (Clupea pallasii) captured on a piece of seaweed at Qualicum beach, Vancouver Island during the annual herring spawn.

Gulls feast on Pacific herring during the annual herring spring spawn in Vancouver Island, Canada

An underwater sculpture acts as the beginnings of an artificial reef in Cozumel, Mexico.

A brain coral photographed during a dive in Cozumel, Mexico where reefs are vulnerable to rising temperatures.

K'omoks First Nation Totem Pole—a historical landmark in Hornby Island, Canada.

A couple enjoys a vibrant post-hurricane sunset in La Paz, Mexico.

Pink flamingos (Phoenicopterus ruber) in Campeche, Mexico. A species that drives ecotourism in the region.

A small coral Hawkfish (Cirrhitichthys oxycephalus) emerges from between the coral in a reef in La Paz, Mexico.

An egg yolk jellyfish (Phacellophora camtschatica) drifts across the ocean surface in Tuwanek, Canada.

The aurora borealis reaches Kitsilano beach, Vancouver. Can you see the big dipper?

Awards

Special Recognition at the OceanPrediction DCC Photo Contest “Ocean’s Beauty” category, 2025

Third Prize at Ocean Exposures Photo Contest “Below the Surface” category, 2024

Photo Contest winner “Botany and Zoology Wellness Initiative”, University of British Columbia, 2021

Photo selected for the Convention on Biological Diversity “Celebrating 25 Years of Biological Diversity” book, 2018

Features & Collaborations

United Nations Convention on Biodiversity — The Nature Conservancy, Mexico — Ocean Nexus — Bamfield Marine Sciences Centre — Marine Mammal Research Unit, UBC — Ocean Equity Lab, Simon Fraser University — Discovery Passage Aquarium — Living Oceans Society — Science Communication Group — Angela Pastificio — BC Children's Hospital —

United Nations Convention on Biodiversity — The Nature Conservancy, Mexico — Ocean Nexus — Bamfield Marine Sciences Centre — Marine Mammal Research Unit, UBC — Ocean Equity Lab, Simon Fraser University — Discovery Passage Aquarium — Living Oceans Society — Science Communication Group — Angela Pastificio — BC Children's Hospital —

Science Communication

Capturing the true value of kelp in British Columbia

Human–kelp relationships are complex, evolving, and often reduced to either conservation or economic use. In this project, supported by Ocean Wise in association with Simon Fraser University and Ocean Nexus, we visited BC’s kelp communities to document their stories.

Through interviews and photography, we met the people shaping these communities and discovered how their work, connections, and values reveal a more holistic, regenerative way of valuing kelp.

The Often-Overlooked Perspectives of Fisher Women

As part of the Ocean Nexus research project 'Listening to fishing communities on climate adaptation in the tropics' led by my colleague Dr. Sieme Bossier, we spent one month in Yucatán, Mexico interviewing artisanal fishers and listening to their perspectives on fishing as a livelihood.

Through this photo blog and video, we share a glimpse into Amada’s life as a crab fisher in Celestún.

Listening to the Perspectives of Artisanal Fishers in Yucatán, México

Climate change adaptations are necessary to safeguard the food security, livelihoods, and cultural heritage of artisanal fishers, yet there is a lack of understanding among policy makers about the adaptation priorities of fisherfolk, and what resources or support they would need to actually implement them.

In this photo blog we highlight some of the perspectives of the artisanal fishers we interviewed and summarize project findings.

Grey Whale Ecotourism in Baja California Sur, Mexico

It’s that time of year again, when people and grey whales head to the lagoons of Baja California Sur for the annual winter event.

Learn more about the importance of sustainable ecotourism.

Marine Initiative – The Nature Conservancy

While working as a Fisheries Project Assistant at The Nature Conservancy in Mexico, I helped develop and translate a national media campaign video that highlighted a conservation initiative for funders.

Uxmal, Yucatán

Get a glimpse of Uxmal – an ancient Maya city in Yucatán, Mexico featuring some of the local wildlife and a cacao ceremony.

La Paz, Baja California Sur

Come along on a dive at a local reef in La Paz, Mexico to observe the small marine life.

Cell Immortalization: How to Immortalize Cells

During my time as a Marketing Assistant at Applied Biological Materials, I wrote, narrated, and produced an informative video on Cell Immortalization after extensive independent research on the topic.

This video received highly positive feedback from viewers.

Calendar Photo Stories

Exploring Cenotes

Slack-liners practicing at Cenote Yaakun, Playa del Carmen, México

Cenotes are freshwater sinkholes in Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula. They’re not only beautiful natural spaces, but also hold historical and cultural significance.

Millions of years ago, the Yucatán Peninsula was underwater among the coral reefs. As sea levels dropped, the fragile limestone ground collapsed, creating rain-filled holes that eventually formed the world’s largest underwater cave system. To the Maya people, cenotes were sacred—they provided water and were seen as gateways to the "inframundo" (underworld). Today, they attract nature-lovers from slackliners, as pictured, to scuba divers. I feel lucky to have dived in these caverns encountering fossilized marine snails, blind fish, and even Mayan pottery and bones!

I took the featured March calendar photo as I tried my new dome lens to get split shots (half over, half underwater).

Fun fact: licking the lens prevents getting water droplets on the photo. I have yet to master that technique… this photo had to be slightly edited to remove water droplets.

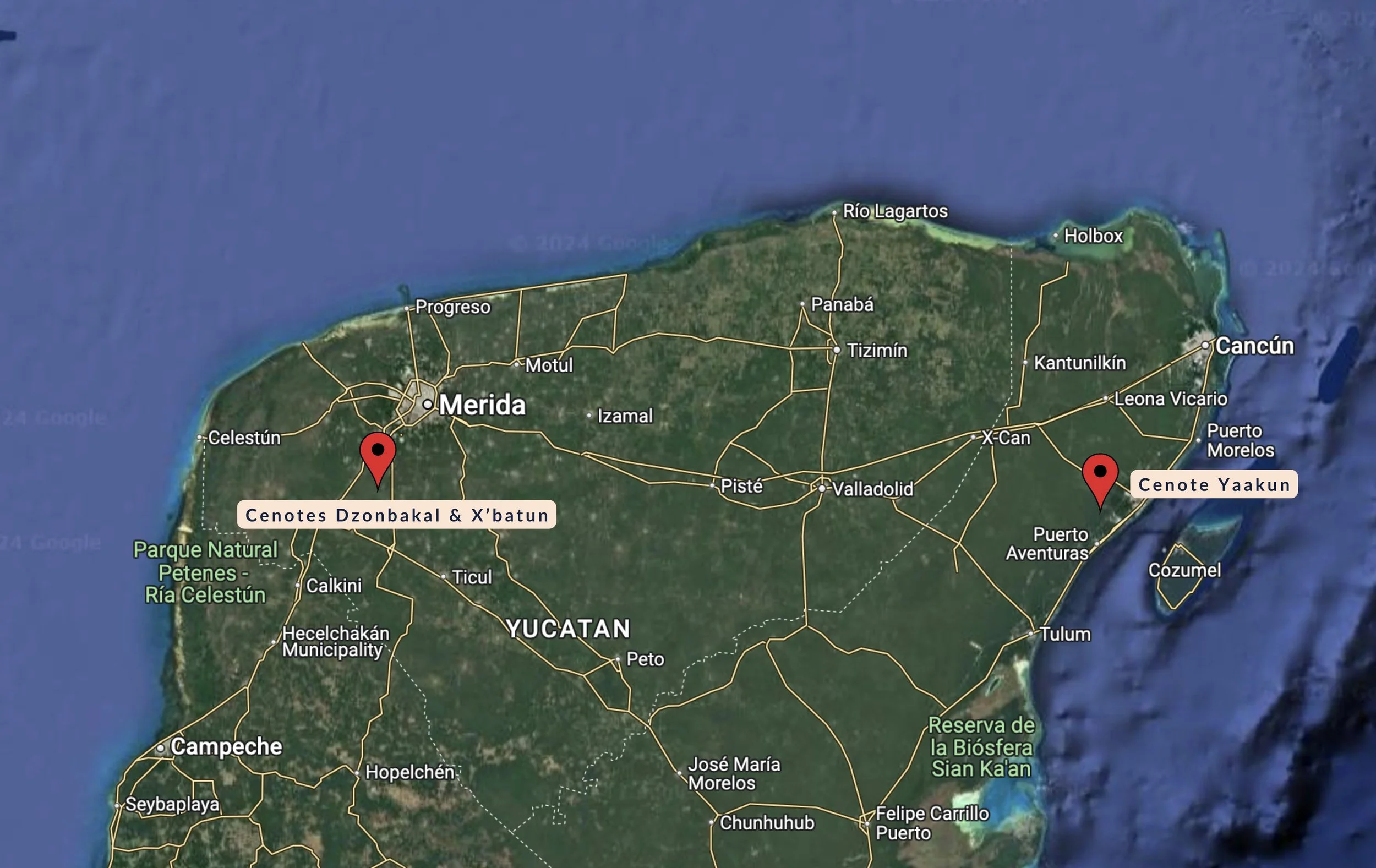

Map of the Yucatán peninsula showing location of Cenotes Dzonbakal, X’batun, and Yaakun

Diving in cenotes usually means driving on dirt roads to arrive at cenotes often managed by local community members, often with mayan decent. Once we arrived we got our scuba gear and tanks set up. Equipment preparation – in my case also including camera gear – is always key prior to a dive. The nerves may be starting at this point, but they are always mixed with excitement. The dive guide explains the cenote layout and the dive plan (how deep we will go, the route we will take, what we can expect to see or experience).

The first dive at cenote Dzonbakal lasted 42 min to a maximum depth of 28.4 m. As we swam away from the cenote entrance, we used our flashlights to guide us around the caverns visiting the known spots where mayan pottery and bones are found. Truly a surreal and eerie adventure!

Pieces of mayan pottery, skulls, and bones inside Cenote Dzonbakal

For the second dive, we headed to the nearby cenote X’batun (my favourite), which was covered in beautiful lily pads at the surface before heading down to the huge underwater world. This dive lasted 56 min, and our maximum depth was 36.8 m.

At this depth, many people experience narcosis due to the nitrogen levels in your blood, this produces a feeling of being ‘high’. In my case, I felt even more at awe of the cenote and felt weirdly comfortable in this massive and spiritual underwater world. Our guide made sure we didn’t spend too much time at that depth for safety, and we began to make our way back to the entrance. That’s when I took one of my best photos and cover feature of the 2024 calendars…

You can appreciate the diver bubbles on the rock ceiling, and the rock debris that collapsed on the bottom from when the cenote first formed.

Our dive guide looking into a cenote crevice as we headed back to the entrance to conclude the dive at cenote X’batun.

Often, cenote photos are difficult to take since it is mostly dark underwater, however here, the light coming from the entrance illuminated the surroundings perfectly.

After these two dives, we headed to the nearby Restaurante Búútuncitoto to refuel with traditional delicious food from Yucatán, a Poc Chuc dish – it tasted like heaven.

Swimming with Whale Sharks

Swimming with a whale shark (Rhincodon typus)—the biggest fish in the ocean—is an undeniably unique experience if done responsibly, and photographing them is no easy task!

The odds were against us on this day; rain from the previous day had pushed the plankton (whale shark food) deeper into the water column meaning the whale sharks were nowhere to be found. We departed from Cancún and headed out into the open ocean. The waves were rough and sea sickness was spreading among our tour boat.

45 minutes went by… we waited patiently…our boat captain noticing we were almost nearing Cuba.

Finally, all of a sudden coming up to the surface for her plankton breakfast was a 12m long female shark—her dorsal fin peeking through the water surface.

It was go time.

I put on my fins and mask, pressed record on my camera, waited for the OK from the captain, and slowly slipped into the water. While battling the strong waves, I tried to keep my hands steady as I pointed my camera towards the approaching whale shark…

As she approached I positioned myself to swim next to her at a safe distance. Only two people are are allowed to swim with a shark at one time, plus the tour guide. This ensures the shark is not disturbed, and that we do not get in her way.

Whale sharks seem like they move slow, but their huge tail propels them forward at a speed that, in the moment, means you have to swim—fast.

As she swam by, I was lucky to get a photo from up close!

Each whale shark’s pattern is as unique as a human’s fingerprint. Although most well known for their impressive size, their dotted and lined patterns are truly iconic & mesmerizing.

I kept swimming behind her at a safe distance from her tail—usually 3m minimum—knowing I would have a better chance of following her safely and capturing some new angles.

Despite the rough conditions that day, jumping in the water and swimming next to the biggest fish in the ocean makes it all worth it.

Swimming with whale sharks is an incredible activity if done while following responsible ecotourism practices. In Mexico, the 2024 whale shark ecotourism management plan states detailed protocols to carry out this activity safely without putting either the sharks or the tourists at risk.

Check out their distance guidelines.

Always do your research and make sure the tour operators you choose follow guidelines that prioritize whale shark conservation and tourist safety.

A month-long research trip to Yucatán

During this research trip, we mainly interviewed artisanal fishers throughout Yucatán to understand their perspectives on the viability of potential climate change adaptations.

During one of our excursions, we travelled by boat to the neighbouring state of Campeche. A local tour guide shared local knowledge and his perspective on fishing and ecotourism—what people in this remote region depend on for their livelihoods.

He took us past the mangroves where we saw this group of flamingos. There were several other tour boats in the area, local tours take tourists out here multiple times a day to watch the flamingos feed along the mangroves.

He also stopped by a few fishers he knew to say hello, they were fishing in shallow water and showed us the crab they had caught. People here depend on the ocean’s resource so much so that some fishers have to resort to fishing using illegal techniques to make ends meet—a common and reluctant reality for some artisanal fishers.

Finally, the tour guide took us to a small island where Mayan pottery washes up to shore. This was an incredibly unique and remote place that we were lucky to see.

Here are more photos from this experience…

Flamingos (Phoenicopterus ruber) walking by the shallow marshes near Isla Arena, Campeche.